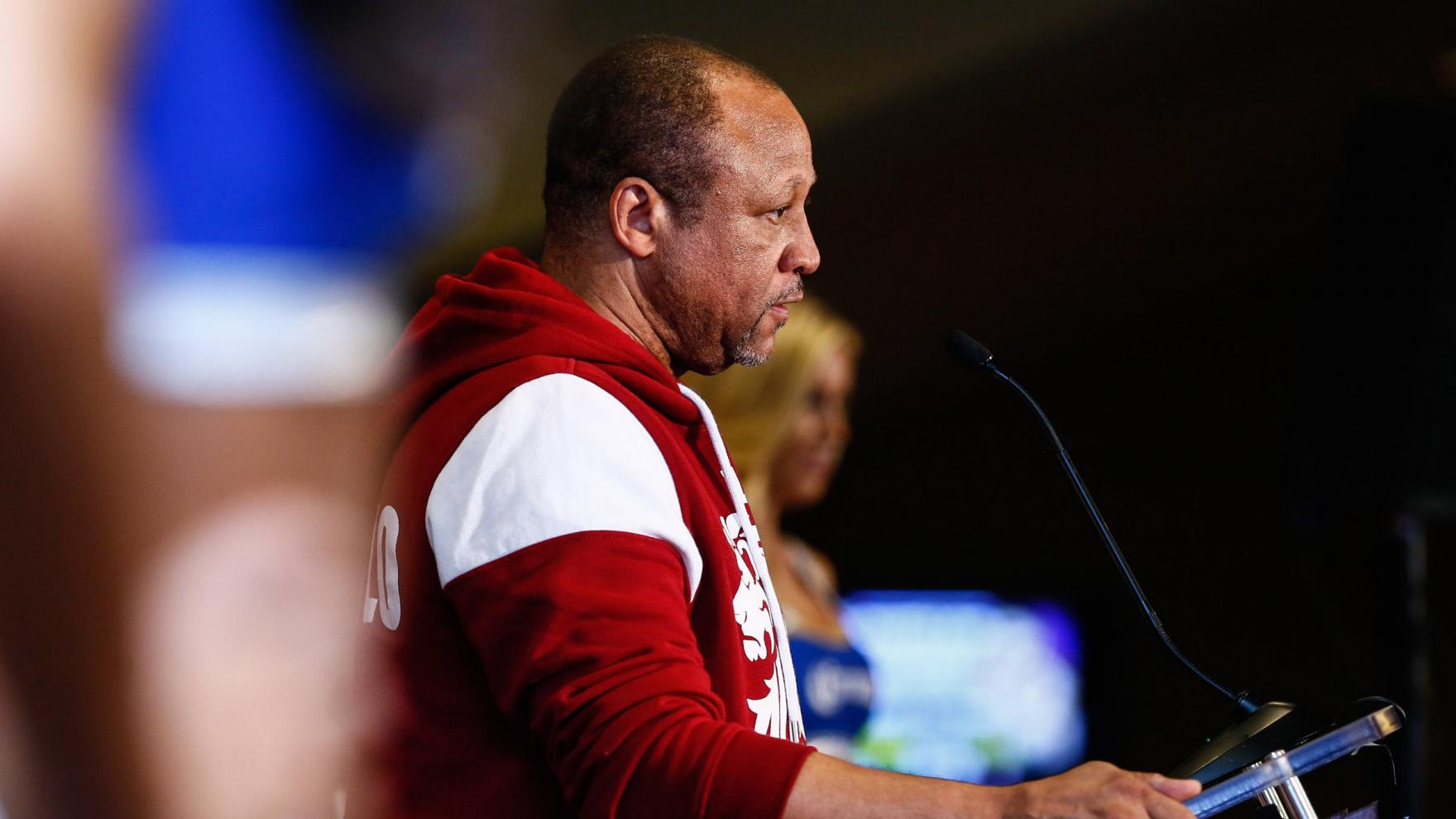

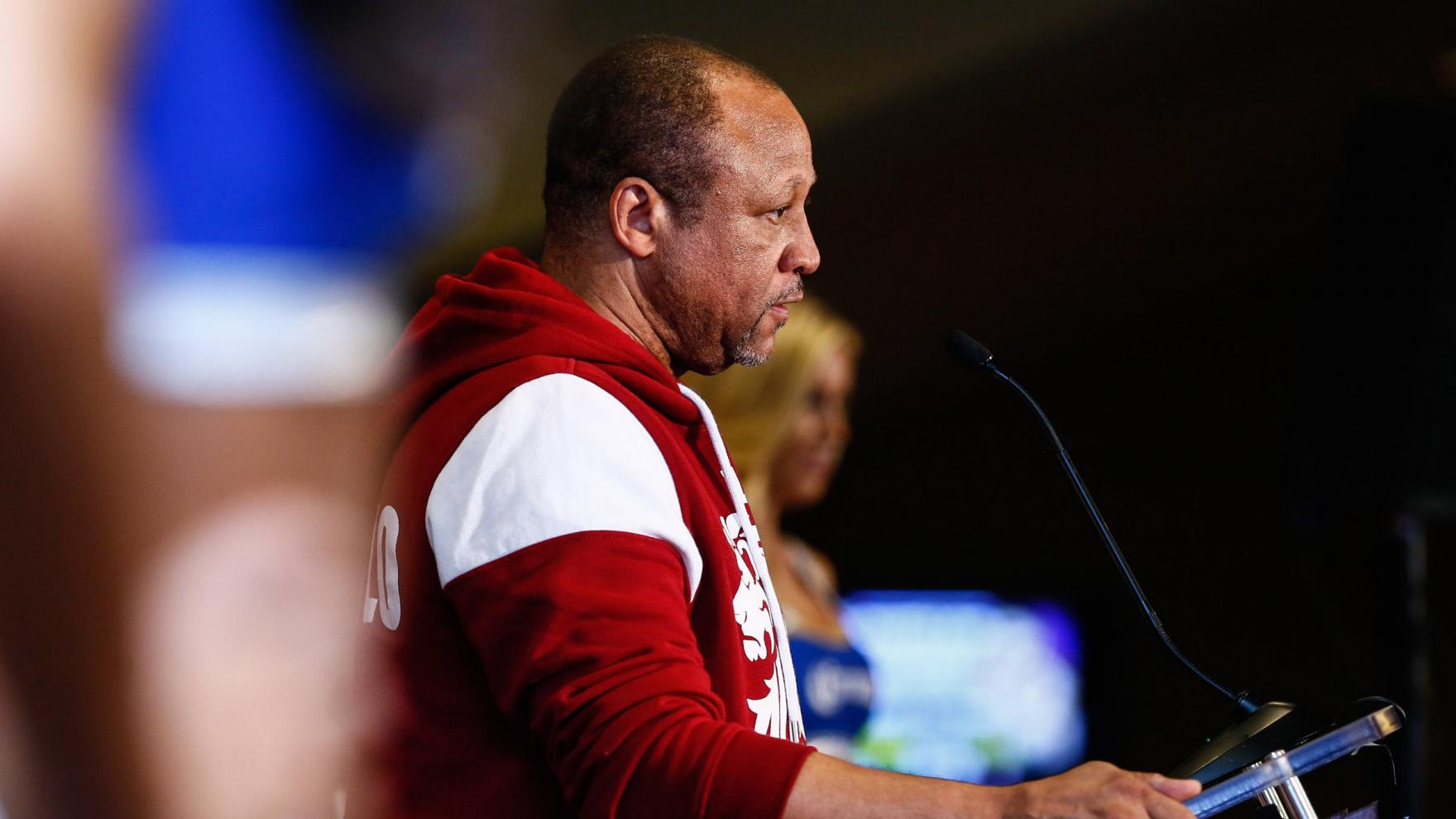

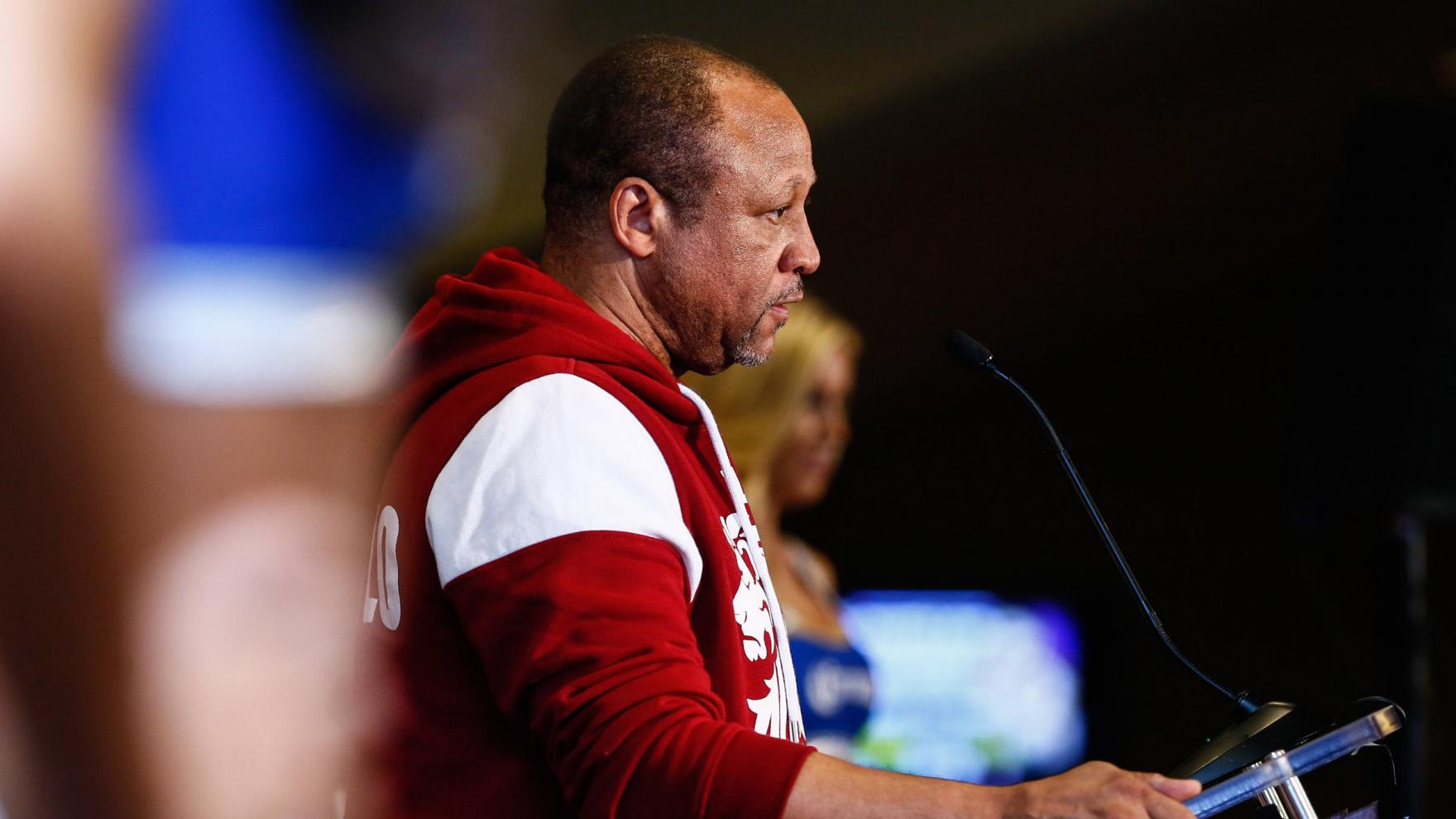

Trainer Ronnie Shields is like a farmer who has tilled the soil and planted the seed. His satisfaction comes when he sees the fruits of his labor. “I love helping fighters realize their dreams,” says Shields, who has become one of the sweet science’s most successful trainers after fighting to little fanfare in the 1980s as a light welterweight title contender. Becoming a champion is what every fighter wants. Once they do that, I’m just happy for them. It fills my heart with joy.”

In three decades as a trainer, Shields, 61, has worked with notables such as Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Pernell Whitaker and Vernon Forrest.

These days, the Port Arthur, Tex. native is most noted for having nurtured the professional growth of twin brothers from his home state.

In Houston-bred Jermall and Jermell Charlo, the WBC interim middleweight champion and former WBC 154-pound champion, respectively, Shields had a direct hand in the ascension of two of boxing’s hottest commodities. “I first met them when they were 10 years old,’’ Shields says. “You could see the potential in both of them even then.”

Although he no longer trains Jermell, Shields has continued to guide Jermall Charlo (28-0, 21 KOs), who returns to his hometown Saturday night to defend his title against Brandon Adams at NRG Arena in Houston. The scheduled 12-rounder will headline the Premier Boxing Champions card on Showtime (9 p.m. ET/6 p.m. PT).

Shields says he never took it personally when Jermell, the younger twin by one minute, decided to open his own gym in Dallas and left him in favor of a new trainer in Derrick Hayes.

“Sometimes people outgrow each other,” Shields says of the 2015 split. “We’re still friends. We still have rapport. I’m actually with him right now. There’s no animosity. It just shows this is a business. If you feel you can do better with somebody else, that’s no fault on him and no fault on me.”

Shields was speaking by phone from the Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas prior to last Sunday’s PBC on Fox-televised main event between Jermell Charlo and Jorge Cota.

In his first fight since losing his WBC super welterweight belt on a controversial decision against Detroit’s Tony Harrison in December, Jermell Charlo kayoed Cota with a fiercely-delivered 1-2 combination in the third round. Jermall, counting down to his own big fight, was at ringside to offer his support.

Shields was in attendance, working as trainer for former super bantamweight champion Guillermo Rigondeaux (19-1, 13 KOs), who scored a devastating eighth-round KO of Mexico’s Julio Ceja to open the PBC on Fox telecast.

“I want to thank my opponent and especially want to thank my trainer Ronnie Shields,” says Rigondeaux, grateful after moving a step closer to regaining a world title.

“Once you get there, the key is to work harder in order to stay there,” Shields says. “I tell all my fighters that you can never get lax because there’s always somebody who wants your spot.”

Inside the ring, Shields had an outstanding amateur career. In 1974, he was the National Junior Olympics featherweight champion and won the 1975 National Golden Gloves featherweight crown. He was also National Golden Gloves light welterweight champion in 1976 and 1978 before turning pro in 1980.

In two shots for the championship, Shields lost a decision against Billy Costello for the WBC light welterweight title in 1984 and lost a split decision against Tsuyoshi Hamada in Japan for the WBC light welterweight title in 1986. He retired in 1988 and took what was learned as a struggling fighter to become one of the sport’s most prominent trainers.

“I adapt to my fighter’s style,” Shields says “These guys are the ones in the ring. Nobody is throwing punches at me. The most important thing is to get the win. Sometimes you’ll face a style that’s not compatible, but an ugly win is always better than a pretty loss. I just try to add when I see things that I feel will help them. But a fighter has got to believe in what you’re trying to do. The hard thing is when they don’t want to accept what you’re teaching.”

Shields currently works with a stable of 13 fighters at his Plex Boxing Gym in Stafford, Tex. He has no outside interests. “Boxing is my hobby and it’s my life,” he says.

Shield has many memorable moments from his career, but says one of the best was when Evander Holyfield knocked out Buster Douglas for the heavyweight crown.

“I was so happy for Evander because he was such a hard-working guy and he was fighting for the heavyweight championship for the first time,” Shields says. “I just remember the emotion coming over me when he got the victory.”

He also has fond memories of Pernell Whitaker’s performance against Julio Cesar Chavez in 1993. The fight resulted in a draw despite many observers feeling Whitaker clearly won.

“That’s when Chavez was considered pound for pound the best in the world,” Shields says. “Everybody saw Pernell won that fight but the judges called it a draw. I just remember when Ring Magazine came out. Pernell was on the cover and the headline read ‘Robbed.’ That said it all to the whole world.”

Shields, who trained under the legendary George Benton for 10 years, also had a close relationship the late, great trainer Emanuel Steward.

“I knew Emanuel since I was 15 years old,” he said. “After I began training my own fighters, I’d call him all the time when I was stuck on something and he’d tell me what I should do. He never held back information. Even when Mike Tyson fought Lennox Lewis and we were on opposite sides as trainers, me and Emanuel went to dinner together that whole week. We didn’t discuss the fight. We talked about everything else. But that’s the kind of relationship we had.”

In contrast to the $55,000 he was paid for his first title fight, Shields says earning power is also at an all-time high for fighters. “Now guys make that much fighting six rounders,” he says.

“Fighters are getting smart and have cut out the middle man to become involved with their own promotions. When Deontay Wilder fights, it’s in association with Deontay Wilder Promotions. Same thing with Manny Pacquiao. Even my guy Jermall and his brother have Lions Only Promotions. That just shows how far boxing has come.”

Shields says his professional life has maintained balance by virtue of a strong family unit. He’s the father of three adult college-educated children, including daughter Erika and sons Winston and Evan. He and wife Mona Lisa have been married 33 years.

“I’ve also got four grandkids and they were all over for Father’s Day,” Shields says. “Everybody cooked for me and we had a great time. Even though I’ve traveled a lot, I’ve always made time for them. I used to coach Winston’s Little League team. When I was there, I was there.”

Shields doesn’t venture to put a date on when he might retire from boxing. “As long as I feel I can help somebody, I am going to do it,” he said. “I’d like to see through all the fighters I have right now. I just want them to have a successful life inside and outside the ring. I want to see them with beautiful homes and no worries in their lives. Seeing them happy and successful, that’s what I get from this.”

PBC press release written by Chuck Johnson